Look around using your mouse, and use the escape key to continue reading.

Model by Sonny Cirasuolo

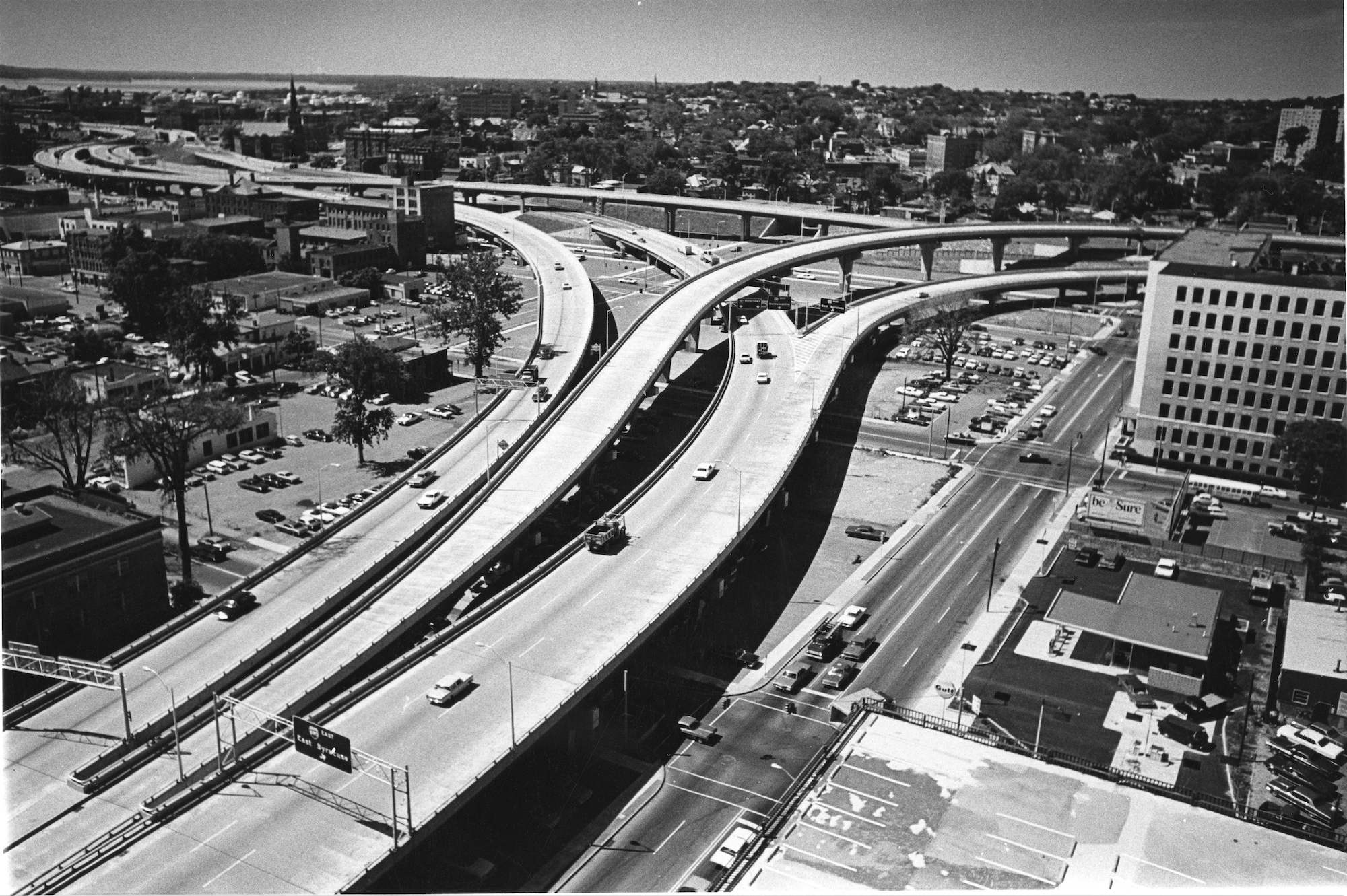

When city and state urban planners in the mid-20th century linked the potential for a federal highway in Syracuse with the potential for “slum clearance” in the 15th Ward, an article in The Post-Standard lauded the program as a route for Syracuse to become the 10th-largest city in the country. Planners projected that the freeway would drive customers and economic growth to the city’s downtown. Today, Syracuse is the nation’s 186th-largest city and consistently ranks as having one of the highest poverty rates in the nation.

A 1935 revision of the city’s charter revoked representation from the 15th Ward, meaning that no Black or Jewish American would be elected to Syracuse’s Common Council for at least 40 years. During those four decades, much of the city and state planning for I-81 and urban renewal transpired with little effort to allow public participation in the decision-making process.

"It was the mid-’60s, and African Americans were still fighting for the right to sit at a lunch counter, let alone the right to sit at the table during economic development discussions that would profoundly affect them,” The Post-Standard editorial board wrote in 2003.

Not allowed a seat at the table, Black Syracusans and allies took to the streets in 1963. Following through on George Wiley of CORE’s ultimatum should Syracuse fail to halt urban renewal, protesters picketed City Hall, attempted to block wrecking crews, and chained themselves to construction equipment. Police arrested 77 protesters that week.

Though the city and state government dismissed demonstrations against the destruction of the 15th Ward, protesters in Syracuse maintained momentum in their fight for civil rights alongside the rest of the country. At the center of the movement in Syracuse was the People’s AME Zion Church at 711 East Fayette Street under the leadership of the Rev. Emory Proctor. Located just a block away from the I-81 viaduct, the former church building — commonly referred to as “711” for its address — was one of the few historically significant structures in the Ward to avoid the wrecking ball of urban renewal.

Starting in November 1963, Proctor and CORE sponsored a series of meetings opposing police brutality. After meeting at 711 in January 1964 to draft a formal complaint against a recent incident of police violence, another march launched from 711’s front door as 150 protesters chanted their way to City Hall and then the Willow Street police station. That same year, one of the first structures to be built under the city’s Community Plaza urban development program was a new “Public Safety” building, now the criminal courthouse building at 505 South State Street.

That protest would be followed by one of the most successful civil rights campaigns in the city rallying against job discrimination by some of the city’s largest employers at the time, including Niagara Mohawk (now National Grid), Woolworth’s, and Carrier Corporation. Jessie Griffin, who moved to Syracuse in 1952 from Georgia, remembers attending NAACP meetings at 711 and marching with Proctor to the Woolworth building on South Salina Street. And it was Proctor who helped Juanita Sales interview and land her position at Carrier, where she worked for 35 years.

On a memorable day in May 1965, 21 activists from Selma, Alabama, came to Syracuse to march and rally against job discrimination at Niagara Mohawk. The crowd that gathered to hear them speak at Clinton Square reached into the hundreds and by one estimate as many as 1,200 people. The following week, Proctor and four other demonstrators sat for more than five hours in front of a Niagara Mohawk exhibit in the War Memorial until police arrested them.