The significance of incorporating equity and community development resources into the state’s plans for the highway’s removal is an effort to restore much of what the state took away from Syracuse’s Black community when the highway went up.

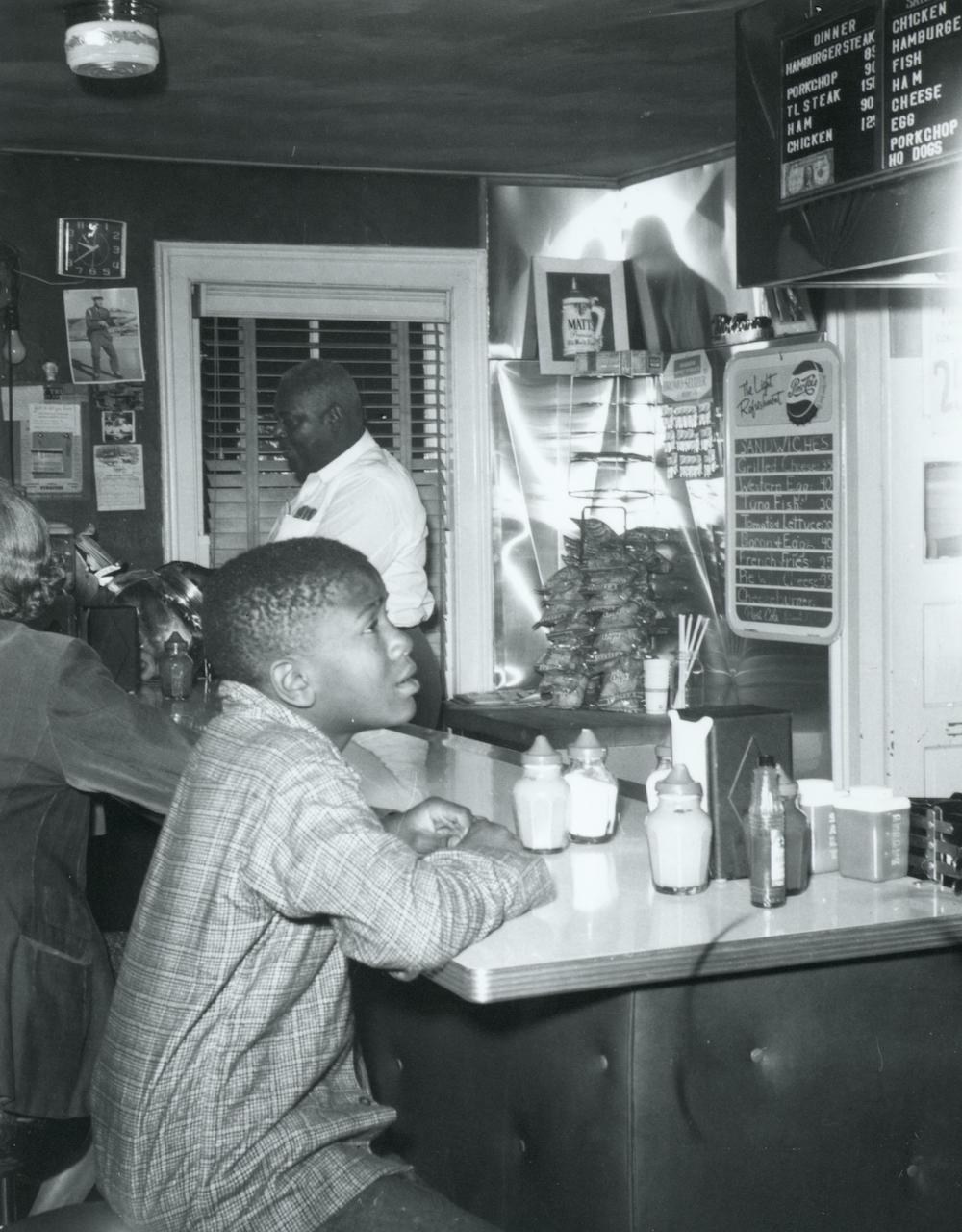

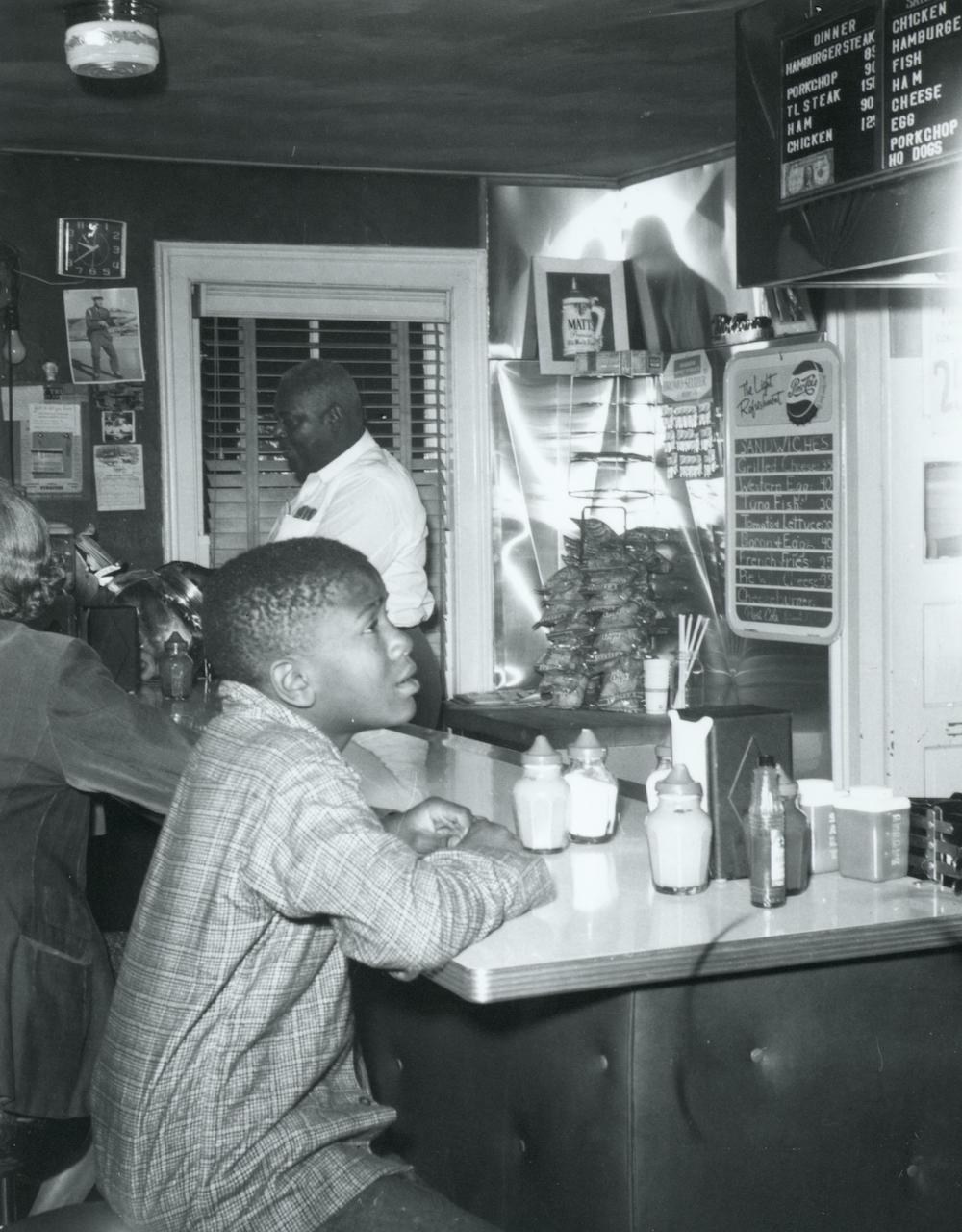

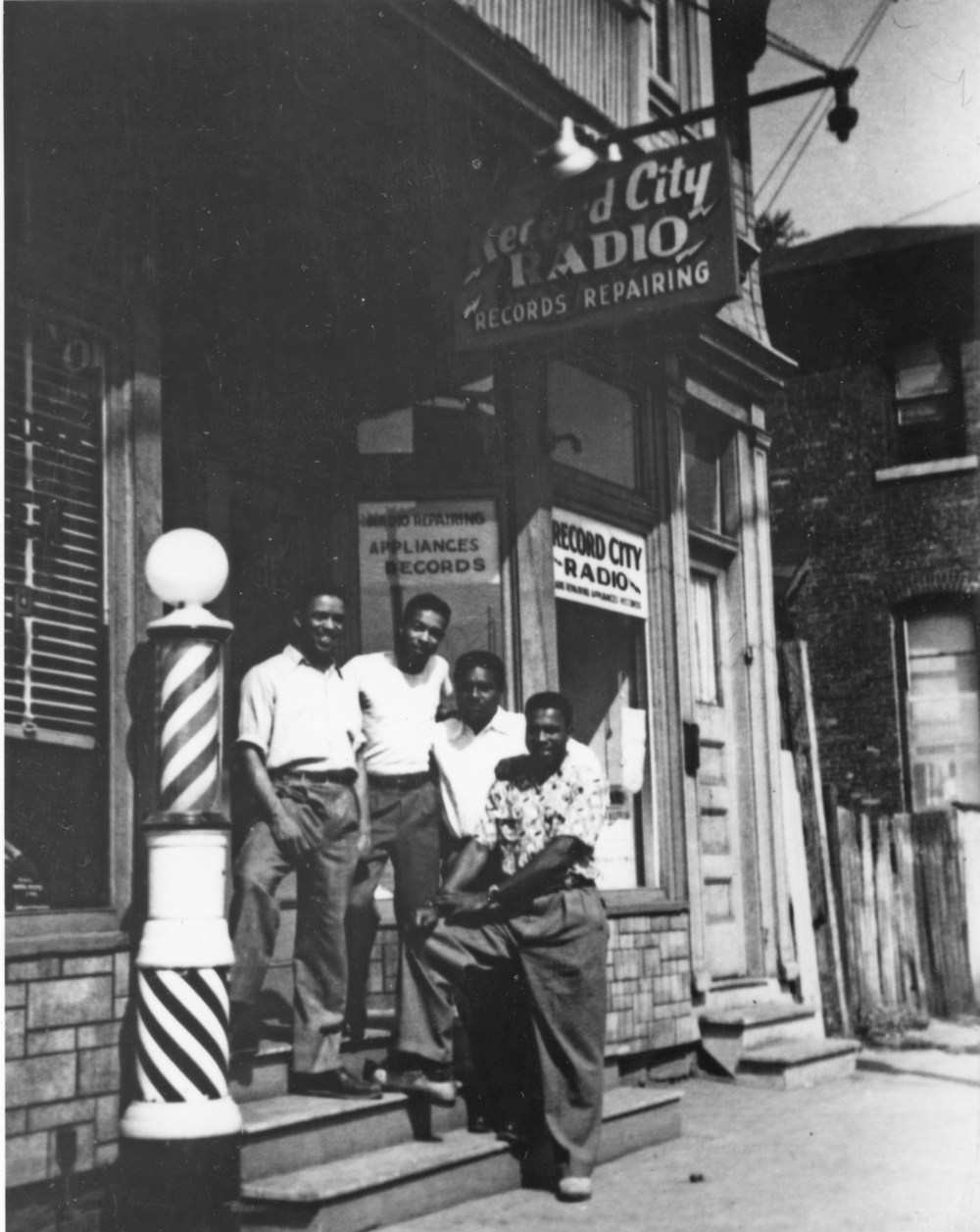

Currie also recalled venues like the Elk’s Club that hosted dances and entertainment on the weekends. In the 2011 documentary The 15th Ward and Beyond, other former residents of the Ward mentioned Black-owned businesses in the area including Mr. Calafaro’s Beauty Shop on Madison and Almond streets, Frank’s Bar and Grill on State Street, George’s Bar on the corner of Townsend and Adams, and others like Mama Craig’s Restaurant, Jackson’s Paper, and Malone’s Barbershop.

Aunt Edith’s was located next to Ben’s Kitchen in the 600 block of Harrison Street, a spot remembered as a central location in the Ward. In fact, on an evening in 1949, a public speech that would incite the Supreme Court case Feiner v. New York gathered a crowd of more than 75 people in front of the A&B pharmacy across the street.

The 1951 Negro Motorist Green Book lists at least 31 of the prominent Black-owned or Black-friendly businesses in Syracuse at the time, including restaurants, taverns, hotels, beauty parlors, barber shops, and night clubs. These 31 locations are a small sampling of the estimated 400 to 500 businesses torn down in the 15th Ward as part of I-81’s construction and the city’s urban renewal efforts.

“There was a lot of businesses that went out of business when they came through with 81,” Currie said. “And [now] there’s nothing there of the 15th Ward — nothing. Everything is Upstate, the university, and 81.”

Many of the locations listed in the 1951 Green Book have been replaced by large-scale buildings and their parking lots, or vacant lots left undeveloped from the 1960s when urban renewal progress slowed. The razing of the 15th Ward proceeded, despite a lack of guarantee for new development, due in large part to city planners and local newspapers’ framing of the demolition as needed “slum clearance.”

“At one point, the military got involved and a Marine tank was used to demolish a few ‘shacks' in the area,” wrote Joseph DiMento, a University of California urban planning and law professor, in a report on Syracuse’s urban freeway. “Newspaper articles described the makings of ‘a possible race riot’ as a result of ‘evils nurtured in slums’ and the 15th Ward as a ‘keg of dynamite.’”

But the city and local newspapers’ depiction of the Ward didn’t match up with the perspective of those who lived there. Currie remembered feeling safe in the Ward, and that when she lived there she and her neighbors didn’t lock their doors. John Williams, a best-selling Black author in the 1960s who grew up and lived in the 15th Ward, wrote about the city in his 1964 magazine article “Portrait of a City: Syracuse, the Old Home Town.” Though he didn’t romanticize the city and remembered Syracuse police occupying the Ward like it was a prison, he wrote that the nature of the Ward was that everyone looked out for each other.

“Ours was a community, despite everything else, in which survival of the other fellow or his children meant survival for you,” Williams wrote. “That is all gone now. Now there’s nothing. Not unfriendliness, just nothing.”

Williams lamented the city’s ignorance of the “great strength” that “emanated from that polyglot community,” and the city’s mistreatment that allowed the Ward to fall into disrepair and then destruction. He saw Syracuse’s abandonment and annihilation of its most diverse community as a great failure common in cities across the country and even across the world.

Bryant of Syracuse University thought back to Williams’ article and that perspective he had imparted. “There’s a distinction between the relationships that forge this community and the space,” she said. “Decrepit buildings didn’t necessarily translate into a dysfunctional community.”