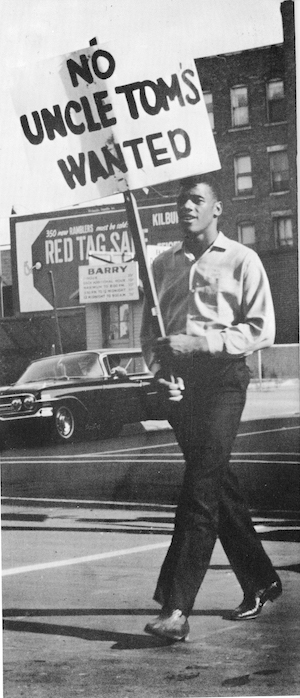

s 200 protesters marched from the People’s AME Zion Church on East Fayette Street to Syracuse’s City Hall, they crossed the city ground where the new interstate highway would soon loom overhead. Protesters’ chants of “freedom, freedom!” carried on the call from only weeks before when, on Aug. 28, 1963, Syracuse protesters boarded a bus at the same church to attend the historic March on Washington. Meanwhile at City Hall, a few onlookers jeered “beat ‘em, beat ‘em,” in return.

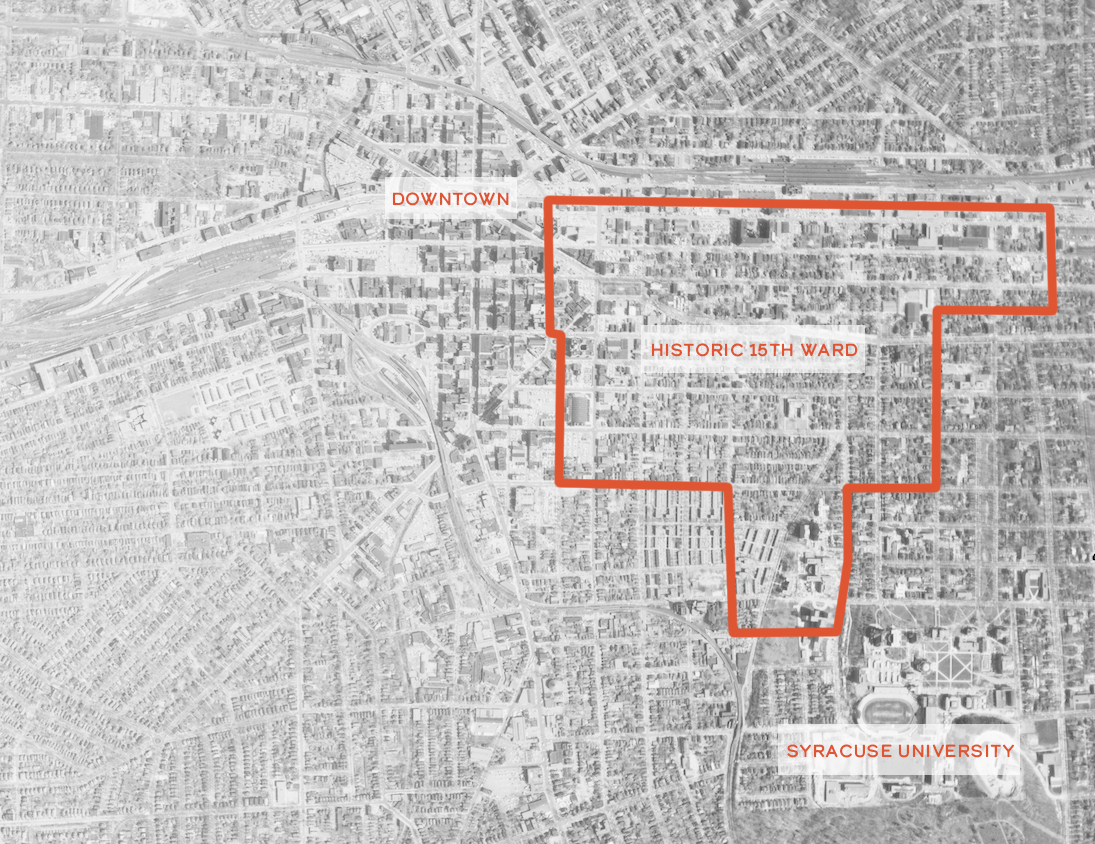

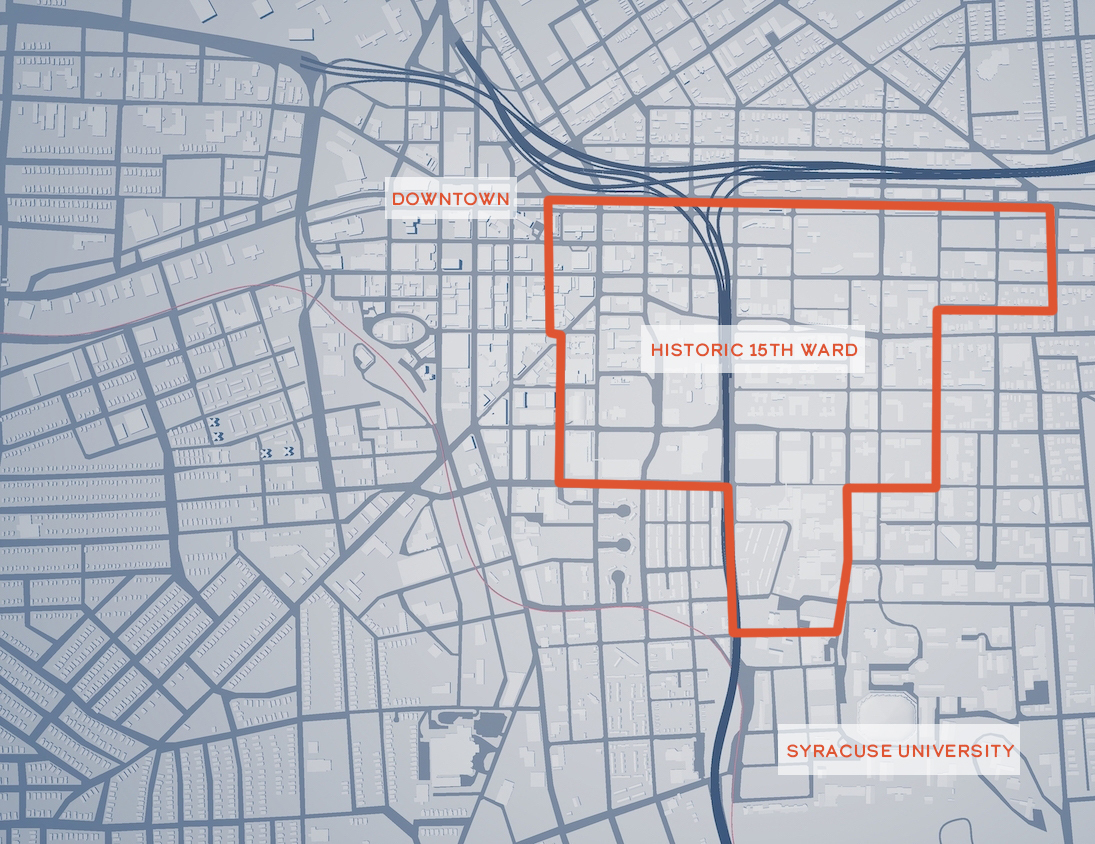

Syracuse in 1963.

The march had gathered in response to the city’s planned construction of Interstate 81 and a slate of urban renewal programs in Syracuse’s 15th Ward. In September 1963, Syracuse’s Congress on Racial Equality (CORE) appealed to then-Mayor William Walsh to halt the demolition of the Ward and the segregated relocation of families that would follow. If not, CORE spokesperson George Wiley announced the “direct intervention of our physical selves into the urban renewal area to halt the urban renewal program.”

Walsh bluntly denied the request.

“I cannot believe that you have fully weighed the consequences of your action,” Walsh said, as reported by The Post-Standard at the time. “As mayor of Syracuse, I hereby request that in the best interest of our community, you withdraw your ultimatum, which is a threat to bring the orderly process of city government to a halt.”

The city and state governments’ “orderly process” would come to be known as one of the biggest urban development blunders in the city’s history — or, as the now-defunct Syracuse Herald-Journal called it, a “Russian roulette multimillion dollar boondoggle of concrete and steel.”

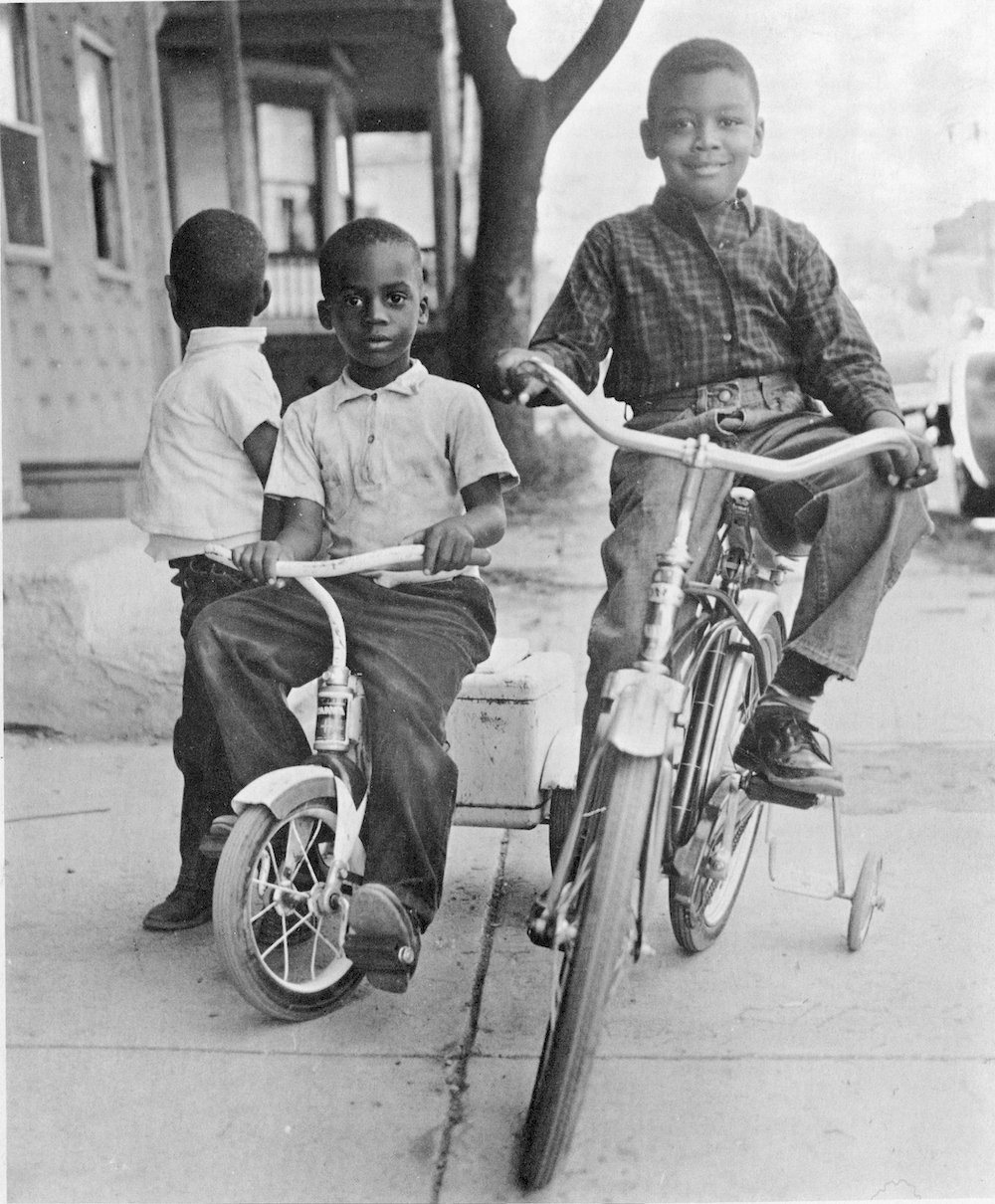

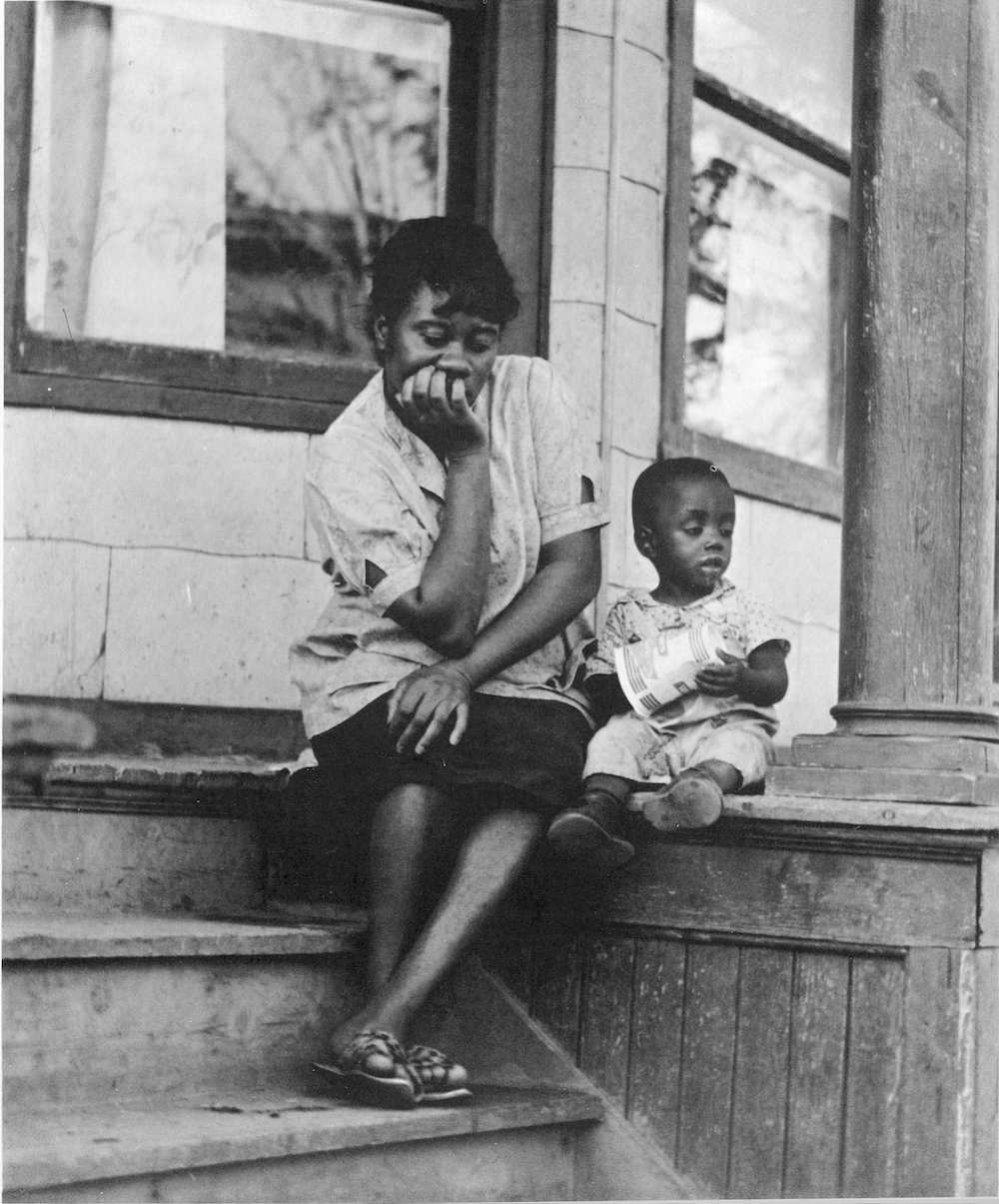

The construction annihilated Syracuse’s historic 15th Ward, which before the late 1960s formed the center of African American, Jewish, and immigrant life in the city. In 1950, eight of every nine Black residents in Syracuse lived in the Ward, which housed a residential neighborhood similar to the rows of early-20th-century, single-family homes still found around Syracuse University and Westcott Street today.